Parents searching for the best way to teach kids Spanish usually land on flashcards and vocabulary drill sheets.

The problem is that children do not store Spanish words as tidy lists. That’s not the natural way any human learns their first language, and it’s not an easy way to learn their second.

The fastest and easiest way for kids to learn Spanish vocabulary is through meaning, imagery, emotion, patterns, and natural repetition inside stories that they actually enjoy.

Let’s dive into what neuroscience, brain studies, linguistic experts, and researchers say about teaching kids Spanish with stories and what makes it so effective.

If your child reads or listens to a bilingual English–Spanish story and hears, “The wolf began to run. El lobo empezó a correr,” they are not just memorizing “correr.” They are picturing a wolf, feeling the chase, and linking the Spanish verb to an exciting moment.

That richer encoding makes Spanish vocabulary stick far longer than isolated word lists or dictionary-style memorization.

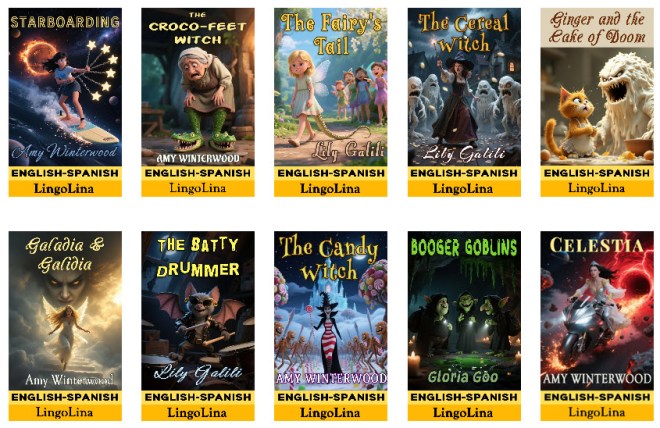

At LingoLina™ we use our NeuroFluent™ Immersion Method, which presents each sentence in English and then in Spanish so kids can learn Spanish naturally through bilingual immersion.

The English line provides instant meaning, so your child always knows what is happening in the story and can easily follow along. When the Spanish line comes right after, your child already understands the message. The new Spanish words attach to that clear scene in the mind.

Spanish stops feeling like a stream of unfamiliar sounds and starts feeling like a language with meaning your child can enjoy.

This is the best form of Spanish immersion because it’s the kind of Spanish your child can understand right away. Researchers call this comprehensible input. It is the fuel real Spanish language acquisition runs on, not quick cramming that fades by next week (Krashen, 1985, 2013).

Putting the same idea into English and Spanish also taps dual coding, giving kids two memory pathways to the same message, which improves recall of Spanish words and phrases without extra effort.

Vandergrift and Baker (2015) found that children remember far more language during listening tasks when the meaning is easy to follow. That’s exactly what bilingual stories do. Because the English comes first, the kids fully understand the meaning, before hearing the new Spanish words.

Because stories repeat common Spanish words in different scenes, you get what’s called spaced reinforcement; a valuable repetition of Spanish words in a natural way, through imagination and meaningful scenes not just through re-reading vocabulary lists. This repetition that strengthens the memory of Spanish words over time.

When you read those Spanish bedtime stories at night, sleep helps lock the new vocabulary in place for tomorrow. Sleep is one of the most powerful tools for memorizing new vocabulary. Especially in young children, whatever they hear before sleep, sticks more firmly in their memory. During sleep, the brain decides what to remember, what to forget, and what to file away.

Reading bilingual English-Spanish stories to kids works so well partly because of how words are stored in the brain.

As kids learn to read, the brain builds a quick “visual dictionary,” so common written words are recognized almost instantly.

If your child meets “bosque” (forest) inside a vivid forest scene again and again, the look of the Spanish word and the imagined forest bind together. Next time “bosque” pops up in a Spanish chapter book or comic, recognition is smooth and quick.

That is why story reading in Spanish outperforms vocabulary drills.

A worksheet might list bosque, but a Spanish story lets the brain glue it to wind rustling through leaves, fireflies, footsteps, and the trees at dusk, which is what makes that word stick firmly in their memory (Riesenhuber, 2015).

Children’s literature expert Janet Bland (2015) notes that stories give children “comprehensible, emotionally rich input,” which is exactly what young brains crave. Clear meaning, real feelings, and vivid images work together so new Spanish words from a bilingual story settle in and stay put.

Gentle repetition of the Spanish words throughout the story then does the quiet heavy lifting. In brain studies, Xue and colleagues (2010) found that meeting the same information again boosts the systems that build long-term memory, including the hippocampus and visual cortex.

Davis and Gaskell (2009) showed that repeated words gradually move from short-term acquaintance to long-term storage, which is why a word your child hears in a story tonight and then again tomorrow suddenly feels familiar.

Second-language research points the same way. Barcroft (2007) found that hearing the same idea in different forms creates richer encoding and stronger memories.

In stories, this happens naturally: your kid will hear a Spanish word in English first and Spanish second, and the same word in different scenes, used in different ways.

That is the heart of LingoLina’s NeuroFluent™ Immersion Method: each English line lands the meaning, each Spanish line links to it, and the gentle, story-driven repetition makes the vocabulary easier to remember and use.

Bilingual English-Spanish stories also light up more of the brain at once.

While your child listens or reads, language areas sync with imagery, and action words can even nudge the motor (physical movement) system in the brain.

If the sentence says, “The boy jumped. El niño saltó,” the brain quietly simulates a jump. That tiny simulated experience makes the Spanish verb more memorable than an isolated list on a page. The Spanish words become more memorable because it feels like an experience instead of an abstract label (Speer et al., 2009; Schacter et al., 2012).

Enjoyment matters here. When kids feel pressure, stress blocks Spanish words from being absorbed and learned. Clear, engaging, vividly described Spanish stories lower stress, so vocabulary and grammar patterns slide in naturally while attention stays relaxed.

Parents often ask why kids forget Spanish words, and the answer is almost always about context and timing.

Kids forget when the first time they hear or read a word it had little meaning, when too much time passes without Spanish again, or when sleep does not get a chance to file the new word after reading.

Bilingual English–Spanish stories fix this by giving each new Spanish word a real scene, then bringing it back later in fresh moments.

Rereading a favorite English-Spanish story is powerful because it reactivates the whole memory network and thickens it.

Even a single month of relaxed, enjoyable Spanish reading can improve spelling, meaning, and grammar, and many previously unknown Spanish words become understandable from context alone.

Age matters when you plan Spanish immersion for kids. Children around four to six do best with short, picture-rich bilingual Spanish stories because their imagination is huge and they need clarity.

Ages six to eight can follow longer scenes and start linking Spanish vocabulary to mental images.

By eight to twelve, many kids are ready for bilingual Spanish chapter books and longer, more complex plots. They pick up verbs, connectors, and descriptive phrases faster as those reappear across chapters.

If a Spanish-only book ever makes your child look lost, do not push. Switch back to bilingual English–Spanish stories so understanding stays solid and motivation stays high. Comprehension needs to come first for Spanish language acquisition to happen (Krashen, 2013).

If you want a simple Spanish learning routine at home, think short, steady, and enjoyable.

Choose bilingual English-Spanish stories your child genuinely wants to hear.

Read the English sentence, then the Spanish sentence.

Add Spanish audiobooks for kids to improve listening comprehension and pronunciation.

When reading out loud, follow the text with your finger to teach kids spelling and quick recognition of written Spanish.

If a kid forgets a Spanish word, smile and meet it again tonight in a new story.

New Spanish stories expand the word bank. Re-reads of familiar stories cement words in memory.

When Spanish learning feels like story time instead of schoolwork, children look forward to it, enjoy it, feel motivated, keep showing up, and the habit does the heavy lifting.

When you compare Spanish learning methods, ask a simple question: Which one gives your child the most understandable Spanish with the least stress?

NeuroFluent™ bilingual English–Spanish stories deliver meaning first, keep anxiety low, and repeat Spanish vocabulary naturally through scenes your child loves.

That is how children build real Spanish, one vivid sentence at a time, until Spanish reading, Spanish listening, and even Spanish speaking feel natural rather than forced.

Try a Bilingual Story Tonight to make learning Spanish fun and easy!

Check out our growing library of free stories, books, and audiobooks.

References

Barcroft, J. (2007). Effects of repetition in vocabulary learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 29(4), 563–588.

Craik, F. I., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11(6), 671–684.

Krashen, S. D. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. Longman.

Krashen, S. D. (2013). Second language acquisition: Theory, applications, and some conjectures. Cambridge University Press.

Nation, I. S. P. (2013). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge University Press.

Ohad, T., & Yeshurun, Y. (2023). Neural synchronization as a function of engagement with the narrative. NeuroImage, 120215.

Paivio, A. (1991). Dual coding theory: Retrospect and current status. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 45(3), 255–287.

Pigada, M., & Schmitt, N. (2006). Vocabulary acquisition from extensive reading: A case study. Reading in a Foreign Language, 18(1), 1–28. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ759833.pdf

Rasch, B., & Born, J. (2013). About sleep’s role in memory. Physiological Reviews, 93(2), 681–766.

Riesenhuber, M. (2015). The neural basis of visual word form processing. Georgetown University Medical Center press materials summarizing research from the Laboratory for Computational Cognitive Neuroscience.

Rojas Ugalde, A., & Vargas Barquero, V. (2021). Enhancing language learning and acquisition by implementing extensive reading. Letras, 69, 123–137. https://doi.org/10.15359/rl.1-69.6

Sangers, N. L., van der Sande, L., Welie, C., et al. (2025). Learning a language through reading: A meta-analysis of studies on the effects of extensive reading on second and foreign language learning. Educational Psychology Review, 37, 96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-025-10068-6

Schacter, D. L., et al. (2012). The future of memory. Neuron, 76(4), 677–694.

Schmitt, N. (2008). Instructed second language vocabulary learning. Language Teaching Research, 12(3), 329–363.

Speer, N. K., Reynolds, J. R., Swallow, K. M., & Zacks, J. M. (2009). Reading stories activates neural representations of visual and motor experiences. Psychological Science, 20(8), 989–999.

Vandergrift, L., & Baker, S. (2015). Learner strategies and performance on ESL listening comprehension tasks. Language Learning, 65(2), 390–416.

Xue, G., Dong, Q., Chen, C., Lu, Z., Mumford, J. A., & Poldrack, R. A. (2010). Greater neural pattern similarity across repetitions is associated with better memory. Science, 330(6000), 97–101.